Part 2 of 2

Mostly, the Civil War was no picnic

Naper Settlement’s Civil War Days was a fun way to do period research. However, I picked up so much information that I’m mostly sharing interesting factoids, rather than anything that will make you a Civil War expert.

Fashion

Sis and I saw some swell clothing at the Civil War Fashion Show. Many of the ladies who accompany the gentlemen reenactors like fashion as much as I do—okay, maybe more—and they have a tremendous commitment to dressing authentically.

Fashionable Yankee Ladies

I bet most of the ladies we saw were Yankees. Though several were more humbly dressed in cotton, we saw plenty of silk, and had it been cooler, we might have seen wool, too. Well-to-do Confederate ladies might have had those fabrics early in the war, but as time wore on, many of them ended up in homespun. Of course you might have met a confederate lady who, like the fictional Scarlett O’Hara, didn’t much care what anyone thought of her, but most ladies would rather not wear blockade-run fabrics, even if they’d been able to acquire them. Some very high-toned ladies learned to spin and weave their own cloth.

Parasol, piping and reticule

If you were lucky enough (or Yankee enough) to have a new dress made, it would almost certainly have piping. In addition to being an interesting decorative detail when done in contrasting fabric as with the dark edges of the dress above, it also helped the garment wear better. In those days, women didn’t have nearly as many outfits as we do now, so a dress needed to last a good long time and hold up well.

Lady with veil

Ladies might have veils on their bonnets even when not in mourning. Veils served as protection against debris while traveling, as well as protecting their skin from the sun. The lady above is wearing a dress with the lowest collar she could possibly wear (during the day, that is) and still be considered respectable. The shawl helps. A proper lady took a shawl with her even in the warmest weather, since to go out “uncovered” would be quite the scandal.

Lady with expensive ribbons

The lady above had a lot to spend on expensive silk ribbon for her bonnet. Also, like many of the other ladies, she wears mitts to protect her hands from the sun.

Work petticoat next to hoop skirt with hem saver

When a lady had physical work to perform, she was likely to wear a corded work petticoat and work corset (one without whalebone stays) so that she could move. If she was only paying calls or going to church, she would wear the whole shebang: linen underclothes consisting of a chemise and knickers, a corset, a petticoat or three, a hoop skirt, possibly with a hem saver to catch any dirt before it could get to her dress, and then the dress itself. Half-sleeves might be worn under the decorative outer sleeves of the dress to give the dress a different look in daytime before one met friends for dinner. Of course, in public, she wore a jacket or shawl, and a bonnet. Even indoors, she always wore some sort of head covering, though it might be just a light fabric.

Confederate after the battle

The Confederate gentleman above no longer has his gray uniform, but his jacket is in the butternut that often served as a substitute. His trousers are ordinary civilian garb. Despite his injuries and the fraying of his attire, he was anxious for us to notice his cravat, since that signaled that he was still a gentleman.

Union camp site

Soldiers’ Food and Supplies

A gentleman from the Illinois Eighth Cavalry displayed samples of the food and other items a soldier might carry as they camped or marched. Union soldiers could often tell that they’d soon be in battle, even before receiving orders. They could count on hardtack, salt pork or beef, coffee, sugar, and salt. If that’s all they got, they were about to head out. If they also received soft bread, cornmeal, dried peas or beans, rice, tea, vinegar, molasses, and vegetables, they’d have time to cook so they might be in camp for a while.

Vinegar can make spoiled food palatable, and maybe even safe to eat. Among soldiers’ rations during the Civil War, they were issued vinegar. Sometimes the food was not as fresh as it should have been, and they’d prepare it with vinegar, which masked the off flavors.

When I said something like, “Great, then you won’t know when you’re getting food poisoning” the quartermaster said that actually, the vinegar was able to kill some of the microbes that cause food-borne illness. Huh. Who knew?

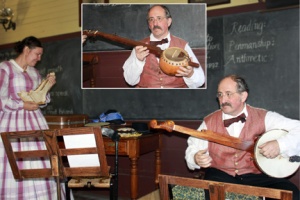

Union kit with canteen, utensils, soap, candles, and game pieces

The number one leisure activity among soldiers was writing letters, or reading letters they received from home, but they also enjoyed reading books, making music or playing baseball, checkers, dominoes and other games.